Pharaoh Ramses II

Pharaoh during Egypt’s golden age, King Ramses II built more monuments and sired more children than any other Egyptian Pharaoh. His celebrated building accomplishments, including the marvels at Karnak and Abu Simbel, reflected his vision of a great nation and of himself as the “ruler of rulers.” He has long been regarded by Egyptians as Ramses the Great and his 66-year reign is considered to be the height of Egypt’s power and glory.

It was Ramses II’s grandfather, Ramses I who had elevated their commoner family to the ranks of royalty through his military prowess. Ramses II’s father, Seti I, secured the nation’s wealth by opening mines and quarries. He also fortified the northern frontier against the Hittites, a tribe out of modern-day Turkey.

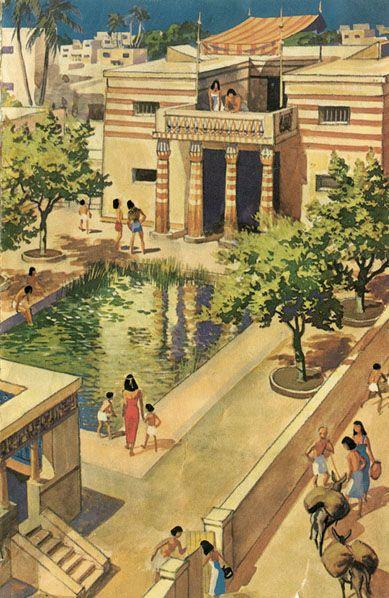

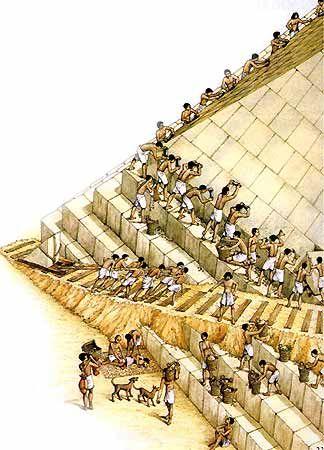

The wealth of Ramses II’s reign is evident in his opulent building campaign, the largest undertaken by any pharaoh. The temples at Karnak and Abu Simbel are among Egypt’s greatest wonders. His funerary temple, the Ramesseum, contained a massive library of some 10,000 papyrus scrolls. He honored both his father and himself by completing temples at Abydos.

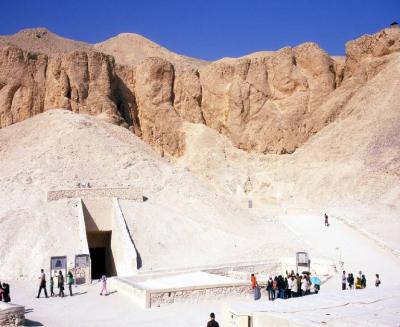

ABU SIMBEL, MONUMENTAL TEMPLE

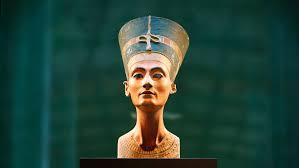

An elevated view of the Ramses temple and the Nile shoreline. Ramses II wanted there to be absolutely no question which pharaoh had built the magnificent temple at Abu Simbel. At its entrance, four 60-plus-foot-tall seated statues of him serve as sentries. Dedicated to the sun gods, the temple extends 185 feet into its cliff through a series of three towering halls. Ramses ordered a second, smaller temple built nearby for Nefertari his wife, because of its remote location. Abu Simbel went undiscovered until 1813.

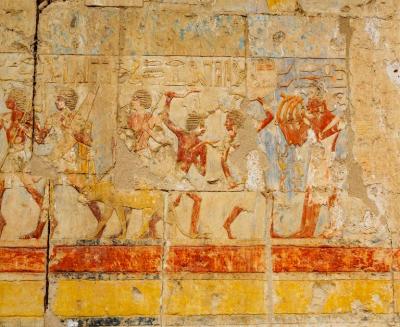

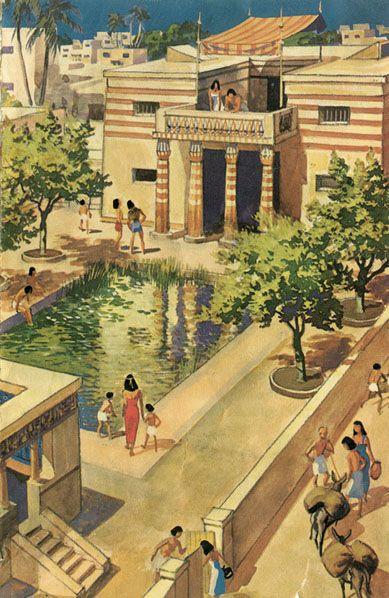

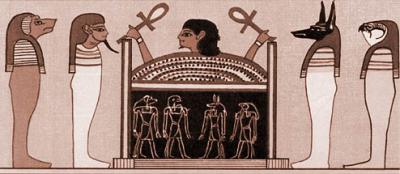

PRINCE KHAEMWASET

Among the more than 100-plus offspring of Ramses II, Prince Khaemwaset truly stands apart. He held the prestigious post of the high priest of Ptah, the patron god of Memphis. Bas-reliefs depict him in his important duty of tending the tomb of Ptah’s sacred Apis bulls in the underground complex known as the Serapeum. Khaemwaset’s larger legacy is his groundbreaking role as one of the first known archaeologists. He was entranced by the thousand-year-old landmarks from the Old Kingdom that surrounded him in Memphis. He inspected and restored several temples and pyramids. At each restoration, he inscribed the names and titles of the building’s original “owners,” as well as his and his father’s names. A millennium after his death, he was revered as a scholar and featured in a series of stories about his accomplishments.

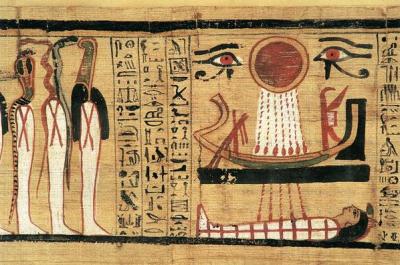

The battle of the Kadesh

The battle is generally dated to 1274 BC from the Egyptian chronology. It is believed to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, involving between 5,000 and 6,000 chariots in total. As a result of the discovery of multiple Kadesh inscriptions and the Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty, it is the best-documented battle in all of ancient history.

The Egyptian Empire under Ramesses II bordering on the Hittite Empire at the height of its power in 1279 BC Ramesses led an army of four divisions: Amun, Re, Seth, and Ptah division. On the Hittite side, king Muwatalli had mustered several of his allies, among them Rimisharrinaa, the king of Aleppo. Ramesses II recorded a long list of 19 Hittite allies brought to Kadesh by Muwatalli.

Muwatalli had positioned his troops behind “Old Kadesh”, but Ramesses was misled by two spies whom the Egyptians had captured to think that the Hittite forces were still far off, at Aleppo, and ordered his forces to set up camp. Rameses proceeded northward. After he reached the mountain range of Kadesh, then he went forward and he crossed the ford of the Orontes, with the first division of Amon. His majesty reached the town of Kadesh the division of Amon was on the march behind him, the division of Re was crossing the ford in a district south of where Rameses was, the division of Ptah was on the south of the town of Arnaim; the division of Set was marching on the road. When Rameses caught two spies they revealed that the king of Hatti has already arrived, together with the many countries who are supporting him, they are armed with their infantry and their chariots. They have their weapons of war at the ready. They are more numerous and ready for battle. They stood at the back of the great Kadesh

After this, Ramesses II called his princes to meet with him and discuss the fault of his governors and officials in not informing the position of Muwatalli II and his army. While Ramesses was talking with the princes, the Hittite chariots crossed the river and charged the middle of the Re division as they were making their way toward Ramesses’ position. The Re division was caught in the open and scattered in all directions. Some fled northward to the Amun camp, all the while being pursued by Hittite chariots.

The Hittite chariot then rounded north and attacked the Egyptian camp, crashing through the Amun shield wall and creating panic among the Amun division. In the Egyptian account of the battle, Ramesses describes himself as being deserted and surrounded by enemies.

Ramesses was able to defeat his attackers and return to the Egyptian line. The pharaoh, now facing a desperate fight for his life, summoned up his courage, called upon his god Amun, and fought to save himself.

The Hittites, who believed their enemies to be totally routed, had stopped to plunder the Egyptian camp and so became easy targets for Ramesses’s counterattack. His action was successful in driving the looters back towards the Orontes River and away from the Egyptian camp, and in the ensuing pursuit, the heavier Hittite chariots were easily overtaken and dispatched by the lighter, faster Egyptian chariots. Although he had suffered a significant reversal, Muwatalli II still commanded a large force of reserve chariots and infantry. As the retreat reached the river, he ordered another thousand chariots to attack the Egyptians, the stiffening element being the high nobles who surrounded the king. As the Hittite forces approached the Egyptian camp again, the Ne’arin troop contingent from Amurru suddenly arrived, surprising the Hittites. Finally, the Ptah division arrived from the south, threatening the Hittite rear.

After six charges, the Hittite forces were almost surrounded, and the survivors were pinned against the Orontes. The remaining Hittite elements, which had not been overtaken in the withdrawal, were forced to abandon their chariots and attempt to swim across the river, where many of them drowned.

Comments